New year, new gear. Time to reflect on the lessons learned during 2019, a year that I remember from its warm and pleasant summer, Greta Thunberg and climate anxiety, Brexit drama, and the “stable genius” of Donald Trump.

On a personal note, one of the highlights of the year was that I left Europe for the first time for a summer holiday in California, USA. I traveled alone, even though a travel companion or an entourage of such would have been nice. Luckily there’s one thing a solo traveller can do at their leisure that’s not so convenient when travelling in company. And that is to binge-read books 🤓.

I read books in their physical form quite infrequently in my 20’s because I was hooked on Wikipedia and too preoccupied with my studies. However, I have picked up reading again in recent years. One of the sources of happiness I have discovered is reading in bed at night by the light of a dim lamp. I have a hunch this might be the hygge the Danish talk about.

I read just for the sake of reading, often times just by opening a book in the middle and following along for a chapter or two. Poetry, mathematics and philosophy work best for this purpose. They make you mighty drowsy, too. Every once in a while a captivating piece of work comes along that I simply devour from head to tail.

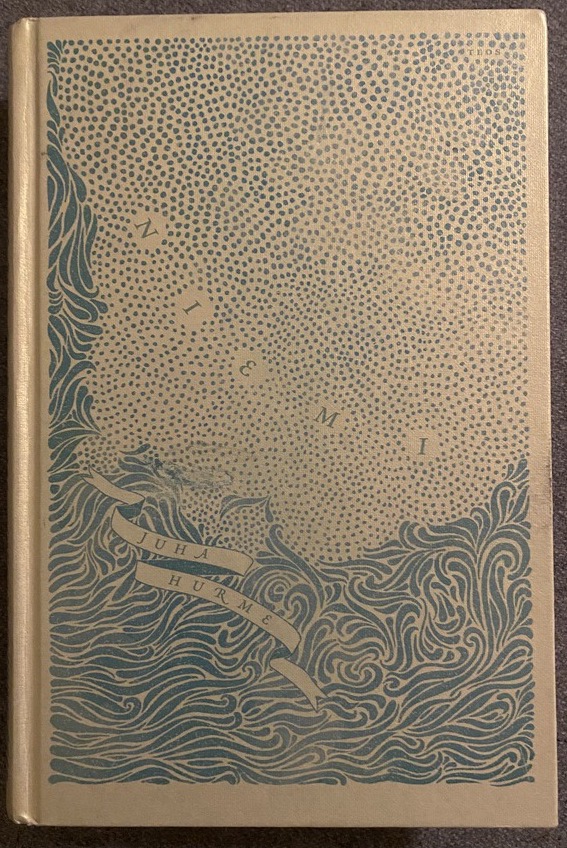

One of those books that I read in 2019 was Niemi (The Cape) by Juha Hurme.

I read The Cape in the desert surroundings of Joshua Tree, CA, and boy was it good. In it, Hurme lays out the history of Finland, starting from the Big Bang, dinosaurs and tectonic movements. Think of it as the literary version of Right Here, Right Now by Fatboy Slim but with a Finnish twist.

After a brief overview of the universe, the book zeroes in on an area it calls the “Cape.” It is Finland, but calling it that would drag along all the baggage of nationalism, so the author took the liberty of rechristening what was called East Sweden by the contemporaries as the Cape. This makes sense as the whole notion of Finland was pretty much invented in the early 1800s where the book ends. Before that, Finland referred to the province that is now called Finland Proper.

The choice for the scope of the book is laudable, as it allows Hurme to focus on the centuries and many unsung heroes that are virtually unknown to Finns. A good example is Sigfridus Aronus Forsius. The dude was mental.

As Hurme is also an active playwright, we are also treated with plays about the same content. The plays Europaeus and Making of Lea about the humanist Daniel Europaeus and the first Finnish-speaking theatrical group headed by Kaarlo Bergbom are examples that come to my mind.

Literary pioneers seem to be a particularly keen topic for Hurme, and I do not wonder why. Stories about rebel underdogs who went against the grain and never got a chance to be included in the canon of high culture are obviously interesting and therefore worth telling.

In addition, Finns tend to have a rather nationalistic view of the world and history. The problem with this is that it leads to a worldview that is quite close to the diagram shown by Conan O’Brian back in 2006 when he took a liking to our country and our president Tarja Halonen. The diagram summarized Finnish history with three points: Finland is settled, Nokia starts making cell phones and the present. It would seem that nothing happened in the intervening millennia.

The book tries to fill the gap and alternates between biographies of Finnish-Swedish thinkers and Hurme’s interpretations of historical writings and poems. The text samples are firsthand evidence about the development of ideas and ideologies at our latitudes. It was a very slow process.

Hurme’s delivery is his typical and lively verbal fireworks but his commentary also reveals a more serious and political side. As Hurme has us to believe, ultimately nothing is indigenous to Finland and therefore purely Finnish. Everything, including the mythology behind Kalevala and the instrument kantele, is imported goods. Let that sink in for a while.

If anything, the one original feature of the people inhabiting the Cape was their stubbornness in adopting novelties other than new vices. The people of the Cape, especially non-lay, had an unbalanced and misguided view of the world surrounding them. For example, the study of angels was promoted to its own science before the enlightenment, and the text samples from the clergy at the time make for a cringeworthy reading.

Reading through the lines, the book is also a commentary about our time, in which humanists lurk in the fringes of the society, technocrats rule and right-wing popularism caters to the unemployed leftovers. Contrasting the rhetoric of present day nationalists with the puritanical preachings of the 1600s about the end of the world and noticing how they are constructed essentially from the same illogical ingredients is reassuring. One needs a factual and balanced worldview. Bullshit is bullshit.

Yet, Hurme is a clear fan of Finland. His thinking goes beyond nationalism to a more inclusive and balanced view of us as a natural part of the world and the universe. And that world is not immutable. I believe this is his core message. Nihil novi sub sole.

If you too are a fan of Finland, make Hurme your homeboy. You will notice that his language is marked by some mannerisms that might be a bit annoying for the pedantic reader. Often times it seems that he cuts verbal corners by throwing in slang or dialectical (Häme?) expressions in the middle of otherwise factual content. Another of his manners is to sneak in his own analyses and interpretations of poems under the guise of narration. You feel like you’re reading his diary notes in the middle of a book that is supposed to be non-fiction in some broad definition of the word. As I am personally not so lyrically nuanced and never found Finnish folklore that cool, I can only respond to Hurme’s poem analyses in the language of California, “I feel you brah!”